By Andrea Strosberg, Instructional Design and Support Specialist, The Alvo Institute

January 28, 2014

Imagine a classroom where most of the students aren’t paying attention to their teacher. Sound alarming? In a blended learning classroom, this is actually the goal. Look closer: five students sit at a cluster of computers, bright-eyed and intently busy; small groups earnestly compare amongst themselves the notes on their clipboards; four other children hardly look up from their work at a hands-on center… And those six who are “paying attention”? Their teacher is guiding them through a challenging series of critical thinking questions, fully engaged in discussion with them while calmly and confidently surveying the other learning going on in the room.

Imagine a classroom where most of the students aren’t paying attention to their teacher. Sound alarming? In a blended learning classroom, this is actually the goal. Look closer: five students sit at a cluster of computers, bright-eyed and intently busy; small groups earnestly compare amongst themselves the notes on their clipboards; four other children hardly look up from their work at a hands-on center… And those six who are “paying attention”? Their teacher is guiding them through a challenging series of critical thinking questions, fully engaged in discussion with them while calmly and confidently surveying the other learning going on in the room.

Achieving the beautiful “hum” of a well-run blended learning classroom can seem like magic, but the master teacher has orchestrated a robust system of classroom procedures to enable all this. The old type of procedures aren’t at play here; students aren’t trained to sit silently at attention, watching the teacher’s every move. Quite the opposite is true: there are many moving pieces to blended learning, and this calls for a new style of procedures.

Yes, it’s important to have a command of differentiation, to understand depth of knowledge and learning styles, to create individualized lesson plans, and to harness the power of a couple of stellar online learning providers. But it’s not enough. The best of personalized learning can only be realized once students are set free by the procedures designed to do so.

At first it may seem counterintuitive; more procedures, rules, and routines actually free the students? Procedures that maximize engagement liberate students, rather than limit them. Shifting the focus toward this type of procedure (and away from wishing to control or manage students) is the goal. Think about the choices we want our learners to be making throughout a class period. We’d much rather see students puzzling over finding the area of an irregular shape than spending precious minutes wondering what to do next, whether it’s okay to move to the next level on the computer program, or if their group will be meeting today. Built into the system should be procedures for everything from technology troubleshooting to appropriate group behavior to getting help, and more.

Look even closer at that classroom: Sasha received an error message in her online learning program but quickly consulted a chart overhead to resolve the issue. When Monica and Jose finished discussing the short story they were assigned, they knew to open a designated folder and begin an extension activity. At the sound of a soft chime coming from the SMART Board speakers, the four kids working with math manipulatives neatly reset the station and moved to a table where they practiced problem solving skills—all without having to scramble for supplies, ask about the page number, or be redirected on their behavior.

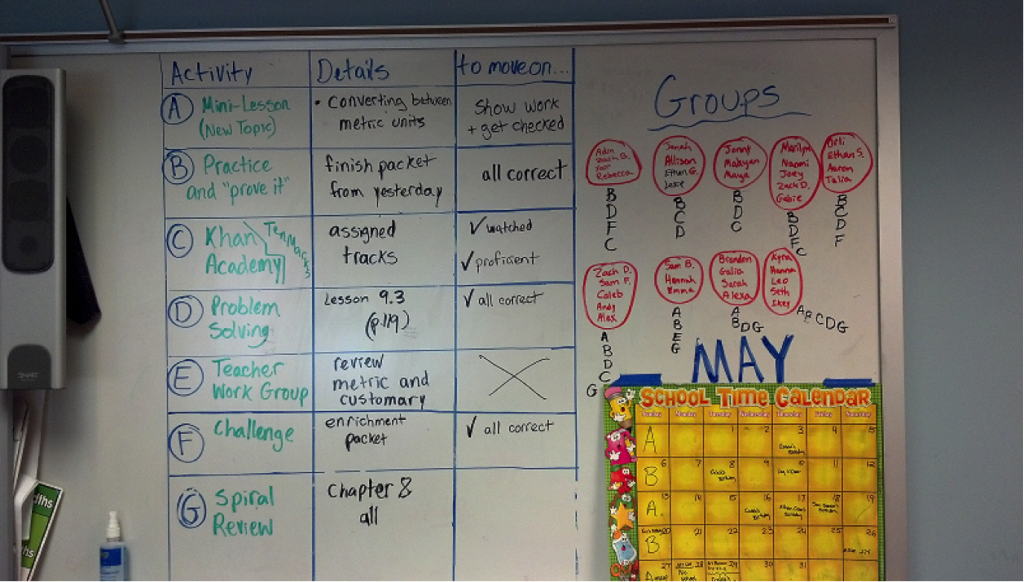

Good classroom procedures give students the autonomy and confidence to know what to do in any number of common situations like those—without the direct involvement of the teacher at that moment. For example, in many classrooms, the use of a centralized chart (perhaps digital) organizes groups,assignment specifics, location of centers, and the flow through a variety of activities. Establishing the procedure that students consult this chart allows for independence. Students begin learning for the day after gathering the necessary information, and make smooth transitions throughout the period in a similar way.

Good procedures like this one set the teacher free—from the fear of chaos, firstly, but more importantly, from the seemingly-innocuous helping or redirecting or the time-consuming “putting out fires” that pull teachers away from what they’re really there to do: actively facilitate learning. Thoughtful procedures take the place of the teacher announcing every assignment aloud or spelling out directions for each activity in real-time, freeing them to use their face time with students to build skills through small group instruction and guide children’s thinking in a way that draws on their teaching expertise. For blended learning to work, there can no longer be a single locus of learning (i.e. the teacher’s physical presence); students must be set free to make choices and take responsibility for their progress within a carefully crafted environment consisting of a variety of individualized learning experiences and sensible procedures.

A list of some procedures we recommend:

- Use colored flags or notecards at computer work stations to signal “need help”, “everything’s fine”, and more

- Appoint supplies captains to streamline gathering materials

- Choreograph (and rehearse) student movement patterns through the room; include rearrangement of furniture if necessary

- Make and teach students to use troubleshooting folders containing useful references and tips for common computer issues

- Create a centralized chart containing all the information students need to answer the question “what am I supposed to be doing?”

- Develop and model codes that stand for the appropriate noise level for different modes of learning

- Prepare students to make decisions about their learning and discuss when, why, and how to transition—When work is complete? Based on the clock? If an activity is too easy or too hard? What next?

(Andrea supports teachers who take part in Alvo’s blended learning programs by creating and delivering a variety of Alvo’s professional development materials. Through webinars and one-on-one support, Andrea works with teachers to develop their lesson plans, blended classroom designs, procedures, and student evaluation practices. Andrea’s teaching experience is in elementary and middle school as well as in Judaic, dual language, and curriculum programs.)

The Alvo Institute 2013©